Black and White by David Macaulay

Innovative Design into the 21st Century

Article 17

by Lyn Lacy 5300 words

(No, dear reader, not that “black and white.” Monochromatic picture books are discussed in Article 13, which was a lot of fun to write. This book titled Black and White (1990) actually has only one double page spread illustrated without color by David Macaulay. The title refers to a riddle “What’s black and white and read all over?” Answer: newspapers, which are important in this story.)

Regarding innovative page and book design, children have not always been accustomed to a variety of design in their books. Ease of printing in the 19th century meant that text was reserved for one page, and an illustration—if one were included—was printed on its own page. See Article 13 for discussion of Wanda Gág (1893-1946), who has been credited for creating the first American picture book with illustrations that flowed for the first time from left to right pages in the classic 1929 Newbery Honor Book, Millions of Cats (1928). Her brother’s hand-lettered text was additionally shaped around her illustrations. Almost two decades later, Virginia Lee Burton (1909-1968) was awarded the 1943 Caldecott Medal for her own classic, The Little House (1942), also with text shaped around double page illustrations, this time in color.

In the early 1960s, a young illustrator in Brooklyn decided he would design a book that looked even more unusual than what had come before, Few people realized over fifty years ago what a groundbreaker Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are (1963) would be.

Once again, Sendak brought new ideas to story and illustrations for the picture book form. Three previous blog articles have discussed ways in which he influenced the genre. Article 4 discussed his honesty about children’s behavior. Max in Wild Things and Ezra Jack Keats’ Peter in The Snowy Day (1962) could not have been more different, but for the first time Keats introduced a little black boy as main character and the next year Sendak portrayed a naughty little white boy as protagonist. Next, in Article 14 Sendak is noted to have startled the public with his monsters, and years passed before critics agreed with him that Max was having the time of his life with the overgrown, friendly furrballs. And in Article 16 the author/illustrator of Wild Things is shown to have ignored traditional magic portals as entrance into another world by having Max transport himself using only his rebellious imagination after being put in a time out.

Wild Things’ size and shape of illustrations changed with each turn of the page, and the audience watched the story unfold as on a stage with opening and closing curtains of white space. Large or small scenes for bedroom, forest, ocean and wild place moved the story along or stopped it on its mark. Sometimes illustrations did not need any words at all, as in the famous “wild rumpus” sequence of three double-page illustrations and at the end, words did not need an illustration. Sendak was a stage manager regulating responses to the various acts in his play.

This variety, ingenuity and playfulness in page design were unusual in 1963. As stated in the introduction for Sendak at the 2003 Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, “He all at once revolutionized the entire picture-book narrative… (and) changed the entire landscape of the modern picture-book - thematically, aesthetically and psychologically.” Margalit Fox in The New York Times (8 May 2012) saluted Sendak as "the most important children's book artist of the 20th century." John Cech has written, “Sendak’s willingness to experiment with varied subjects and stylistic modes contributes to the uniquely defining presence that his work has among contemporary children’s books. In fact, it is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine children’s literature today without his works and the children who inhabit them.” (Angels and Wild Things: The Archetypal Poetics of Maurice Sendak, 1995, p. 3).

Publishing improvements during the mid-twentieth century allowed creators of picture books more freedom to imagine an increasingly wide variety of book and page designs. The picture book was beginning to be recognized as having unique canvases to play with – horizontal or vertical or square pages, single page illustrations or double page spreads, front and back covers advertising what is inside, endpapers that can set a mood, front matter where the story itself may sometimes begin and a body of content requiring the wedding of text and illustration.

The art and publishing worlds of the second half of the 20th century were fertile ground for new ideas, and Sendak’s contemporaries were also playing with picture book design. Marvin Bileck (1920-2005) in the 1965 Caldecott Honor Book, Rain Makes Applesauce (1964), combined silliness of poetic text by Julian Scheer with fanciful illustrations that danced in and around the words. In Thirteen (1975), with words and pictures by Remy Charlip (1929-2012) and Jerry Joyner, thirteen little vignettes were illustrated on double page spreads, each one changing to tell its own story as pages are turned. Eric Carle (1929-) added to his brilliant collages such playful design features as holes eaten through all the pages for The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969), chirping in The Very Quiet Cricket (1990) and twinkling lights for The Very Lonely Firefly (1995).

In 1990 a well-known, award-winning illustrator (1979 Motel of the Mysteries above) created another new kind of picture book. Black and White by David Macaulay (1946-) shocked the public in much the same ways that Where the Wild Things Are had done thirty years before, this time with a nonlinear textual and visual narrative. Macaulay was the author/illustrator of over a dozen books about architecture, design and the ways things worked, and he now turned his meticulous eye for detail and sense of humor to a completely new kind of mind-boggling work of fiction.

In his 1991 Caldecott Medal winner, he asked much of the audience with a storytelling puzzle of four stories, each with its own space blocked out on double page spreads and rendered in its own artistic style—“Seeing Things” (a boy on a train), “Problem Parents” (a family), “A Waiting Game” (commuters with newspapers), “Udder Chaos” (some cows that had their introduction in Macaulay’s 1987 picture book, Why The Chicken Crossed the Road, which also featured Desperate Dan, who had escaped from a train that was taking him to jail, so watch for him to loosely tie the four stories together).

The unique design of intertwining stories on each spread annoyed and outraged many adults who tried to read it aloud to a young picture book audience. The book was far too sophisticated and challenging for none but the most discerning group of young people. If Sendak’s book was likened to watching a stage play unfold page by page, then Macaulay’s was like watching four television channels simultaneously. After many years of sharing this book with youngsters, here was a hint for the beginning: starting with the cows’ story, preface with “meanwhile” before reading the other three. The strategy helped at the onset even though it soon fell apart. The stories themselves may have appeared continuous as pages are turned, but visuals intersected at various pages in the book, and in case an audience thought it had figured out the entire plot, an illustration on the last page suggested another way to interpret it.

In his profound 1991 Caldecott Acceptance Speech, Macaulay said exactly that—“It all depends on how you look at it.” He also said, “The subject of the book is the book,” “It is designed to be viewed in its entirety, its surface read all over,” and “We don’t have to think in straight lines to make sense.” He issued a clarion call for a new mindset about visual literacy headed into the 21st century and explained four crucial experiences that made the book valuable for children—visual perception, visual-verbal connections, holistic thinking and risk taking. Answering his call were illustrator Lane Smith (1959-) and author Jon Scieszka, with The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales (1992) and The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs! (1996), both fractured fairy tales with unconventional pages of twisted points of view and an eclectic mixture of text and pictures.

All these inventive book makers led the design revolution into the 21st century, when illustrators below continued to play with the picture book format, sometimes breaking rules completely with audience participation, filmic or sculptural qualities (however, pop ups and other mechanical/interactive books are a different genre and will be discussed in a future article.) Many thanks for help with several titles reviewed below to fellow enthusiast Travis Jonker of “100 Scope Notes” at School Library Journal for his annual column “Wildest Children’s Books of the Year.” Enticing to think that a 21st century evolution might be handmade illustrations combined with technologies such as three-dimensional printers, immersive images and/or virtual reality. Who knows.

2001 David Wiesner (American, 1956-), Author and Illustrator. The Three Pigs, Clarion Books

Wiesner’s significant contributions to 21st century fantasy in picture books can be compared to none other than Sendak. The prescient Wiesner, known internationally for his phenomenal fantasies, had already firmly planted his feet headed toward the 21st century with work he began in the 20the century—including 1989 Honor Book, Free Fall (1988), 1992 Medalist, Tuesday (1991) and 2000 Honor Book, Sector 7 (1999). (His use for panels of all sizes with engaging viewpoints and an abundance of details was well known, as in Tuesday above.)

His 2002 Caldecott Medalist about The Three Pigs started out formally—the original tale was constrained tightly within white margins—before the illustrations became free-floating as pigs escaped to explore across double page spreads that defied the spaces they were supposed to inhabit. The pigs folded a page into a paper airplane, went exploring other stories, and picked up the Cat and the Fiddle and a mighty Dragon along the way. In this freewheeling visual narrative that turned traditional storytelling on its head, the pigs change appearance according to which story they had slipped into and their thoughts and dialogue were sometimes in speech balloons directed off the page to the audience. Wiesner also received a 2014 Honor Book award for Mr. Wuffles! (2013), released I Got It! in 2018 and Robobaby in 2020. See also Chapter 5 for Flotsam (2006), the author/illustrator’s 2007 Honor Book.

2002 Eric Rohmann (American, 1957-), Author/Illustrator. My Friend Rabbit, Roaring Brook Press

In his 2003 Caldecott Medalist, Rohmann had outsized proportions for his animals squeezed into the pictures until finally, he turned the book sideways into a double page vertical spread in order to stack them one on top of another. Jacques Duquennoy did the same for board book Little Ghost Party (2013), which was tilted so that thin chains inserted into the ingenious illustrations turned things around to create different motions and moods.

2004 Mo Willems (American, 1968-), Author/Illustrator. Knuffle Bunny: A Cautionary Tale, HyperionWillems incorporated enhanced digital photographs of street scenes for backgrounds in his 2005 Honor Book, the first of his three Knuffle Bunny books. The author/illustrator wrote about his Brooklyn brownstones and laundromat: “"Each photograph was taken using a shot list that matched preliminary sketches of the layout of the book. The photos are heavily doctored in Photoshop software (in which) sundry air conditioners, garbage cans, street trash and industrial debris were expunged…in addition to changing the photos to their sepia tone.”

Willems then layered his own comic book art and speech balloons for Trixie and her father into the photographs, often extending outside the field of action onto green margins where text is informally scattered above, below or to the side. He explained: “The sketches were made by hand, then colored and shaded in Photoshop and placed into the photographic collages, also using Photoshop.” The resulting page design was a “melding of hand-drawn ink sketches and photography” that was uniquely suited to this story because portrayal of a toddler’s “boneless” meltdown over a lost toy was, quite honestly, funnier in a cartoon happening to someone else, but the realism of the photos reminded the audience how true to life such an event can be. The illustrations were particularly intriguing when the sketches were actually created to interact with the photography, as in scenes in which the cartoon of Trixie’s dad was rummaging in and around a photographed clothes dryers to find the lost toy.

Willems went on to create a 2008 Caldecott Honor Book, Knuffle Bunny Too: A Case Of Mistaken Identity (2007) and Knuffle Bunny Free: An Unexpected Diversion (2010). See also Leonardo, the Terrible Monster (2005) in chapter 5 and Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! (2003) in chapter 6.

2006 Shaun Tan (Australian, 1974-), Author?Illustrator. The Arrival, Arthur A. Levine

Tan’s graphic novel for all ages was a fantastic wordless masterpiece that portrayed not only the surreal experiences of one immigrant in a new land but also the terrors he and his fellow immigrants faced in their homelands. The book was in six parts, each telling the back stories of war, unseen monsters, slave masters and robots with incinerating vacuums, interspersed with scenes of friendship, compassion, joy and hope in the new land. The layout was similar to an old photo album and indeed, endpapers had sixty photographs of men, women and children from around the world at the turn of the 20th century. Pages of small episodic illustrations were interspersed with stunning double spreads of landscapes, seascapes, cityscapes, all incorporating symbols and bizarre permutations of a new civilization. Such a brief review does an injustice to the bizarre beauty of the intricacies found in this unique book.

The illustrator had explained in his website’s essays about planning for the book’s surreal content: “Removing words, character identity, any precise notion of time or place, and also hovering between realism and the dreamlike softness of drawing…allows the reader to interpret the story in their own way, and at their particular pace or level of understanding…The fact that the book is intended to look like an old photo album, with its simplified layout and sepia-tone naturalism, hopefully adds to this sense of open interpretation.” (excerpted from “Words and Pictures, an Intimate Distance,” ABC Radio National’s Lingua Franca, 2010, and “Strange Migrations,” IBBY Conference Keynote, London, 2012). Tan achieved another black-and-white masterpiece with Cicada (2019). See The Red Tree in Article 4.

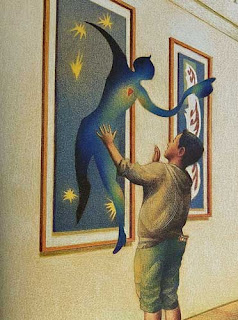

2007 Brian Selznick (American, 1966-), Author/Illustrator. The Invention of Hugo Cabret, Scholastic

Selznick’s 2008 Medalist was an illustrated novel for children ages 9-14. The book had the size of a novel (6”x8”), the heft of a novel (533 pages), and the length of a novel (26,159 words) with 158 pictures (as stated on page 511). A steampunk stage was set in a 1931 Parisian train station with its steam locomotives and enormous clocks, an automaton, film maker Georges Méliès and his 1902 French adventure film, “A Trip to the Moon,” for the coming-of-age story about an orphaned boy hiding in the station until a young girl and her grandfather offered him an important role to play in history. Viewpoints were askew, from aerial dissolves to closeups of Hugo’s eye, all formally framed by black borders and in the Brief Introduction, the author asked the audience to pretend to watch a movie since indeed, many illustrations in sequence created a cinematic effect.

An initial wordless sequence of twenty-one double page spreads and eighteen exciting double page spreads toward the end were the only two lengthy displays of illustrations. Because of its visual sequences, the book was chosen by the Caldecott Committee, but it might well have been under consideration by the Newbery Committee instead because of its novel-length text. Hugo Cabret is a genre-defying, boundary-buster of design that was conceived like no other before and simply shatters all contemporary conventions.

Selznick had written, “I met Maurice Sendak. His words were simple but powerful: ‘Make the book you want to make’…I wanted to create a novel that read like a movie. I looked to picture books for the answer. Remy Charlip posed for me as Georges Méliès because of his uncanny resemblance to the filmmaker… Even though Hugo Cabret is a book about movies, and it’s told like a movie, the main concern is still the book.” Selznick continued with his unique design in Wonderstruck! (2011), The Marvels (2015) and Kaleidoscope (2021). He created a new design for Baby Monkey, Private Eye (2018) reviewed below.

A graphic novel for ages 9-14, Wood’s coming-of-age adventure was handsomely drawn in panels of all sizes throughout its 175 pages. The author/illustrator moved the story along quickly with many twists and turns for two boys in danger from the minute they left school. Wood wrote, “Creating a graphic novel has been my obsession since I was very young (I didn't realize it would take four-and-half years.) Into the Volcano was drawn and painted entirely on an Apple computer with digital media, Corel Painter, Adobe Photoshop and the Wacom digital tablet with stylus. In my experience, digital art is not faster. However, it is more flexible.” The art was not the usual manga or comic book style for graphic novels and was definitely a change from Wood’s picture books, such as 1986 Caldecott Honor Book, King Bidgood’s in the Bathtub (1985), created with his wife Audrey Wood.

2009 Emily Gravett (British, 1973-), Author/Illustrator. The Rabbit Problem, Paper Engineering by Ania Mochlinska, Simon & Schuster

A pair of rabbits had a pair of kits who grew to have babies of their own and so on and so on until the bunny population (a result of the Fibonacci sequence) exploded in a pop-up at the end. The story was formatted to be looked at lengthwise as a calendar, with die-cuts, watercolor illustrations, hand-lettered scribbles for daily events, and little fold-out novelties (invitations, a carrot recipe, a baby rabbit book with tiny ultrasound of the twins) glued to pages for each month. Gravett wrote, “I produce my works by drawing different elements of each page on paper, then scanning it into my computer and assembling the finished page in Adobe Photoshop. This way I can control the page design, and keep it all looking fairly fluid.”

2012 Adam Rex(American, n.d.), Illustrator. Chloe and the Lion, written by Mac Barnett, Little Brown

A picture book that may mark the first time an author tried to fill in for the illustrator. So while the book itself was in progress, the two creators argued over the direction it should take, and things did not go very well. Equally intriguing was Corinna Luyken’s The Book of Mistakes (2017) in which her artistic imperfections were noted in the text and turned into something else, so the story took off into new directions.

2012 Sonja Wimmer (German, n.d.), Author/Illustrator. Jon Brokenbrow, Translator. The Word Collector, Madrid: Cuento de Luz

Luna was a young girl who lived in the sky, where she collected beautiful, friendly, delicious, magnificent words that floated up to her from the world. Her words were personified by being whimsically placed around the pages, floating and flying in and around images so that they glowed with a power all their own. When people stopped sending their words up to her, Luna descended to leave words of love and hope and when she was finished, people again shared words with her and with each other. Brokenbrow also translated Wimmer’s The Magic Hat Shop (2016).

2013 Øyvind Torseter (Norwegian, n..d.), Author/Illustrator. The Hole, Enchanted Lion Books

Eric Carle made die cuts an intriguing way to tell a story, and Torseter placed a little hole running through his book that moved into and out of the story. Another hole in Look! (2015, Owl Kids Books) by Édouard Manceau invited the audience to look at the world with fresh eyes.

2014 Matthias Picard (n.d.), Author/Illustrator. Jim Curious: A Voyage to the Heart of the Sea, Abrams

A boy’s wordless underwater adventure in a large picture book/graphic novel had incredible 3-dimensional detail in illustrations. In Leo Geo (2012) author/illustrator Jon Chad created a factual, similarly fantastic visual journey to the center of the earth and back. Wonderfully bold in design, the long, skinny size of the book mimics the tunnel Leo took into the depths.

2014 Cybèle Young (Canadian, 1972-), Author/Illustrator. Out the Window, Groundwood Books

The simple concept of the page turn was cleverly transformed when Young designed the first half of the story around the main character’s attempts to see his bouncing ball fly out the window and, once the book was flipped over topsy-turvy style, the second half revealed a crazy parade of machines and hybrid creatures. In Some Things I’ve Lost (2015, Groundwood Books), Young designed everyday objects that morphed into photographs of meticulously sculpted paper crafting on fanfolds that extended into horizontal panoramas of what appeared to be fantastic underwater sea creatures.

2016 Richard Byrne (American. n.d.), Author/Illustrator. This Book Is Out of Control! Henry Holt

A remote for a new toy proceeded to control other things on the page until the audience helped Ben and Bella put everything right again. A dog in Byrne’s previous picture book, We’re In the Wrong Book! (2015) likewise bumped the two children from a potato sack race into other books they must travel before they got home again. Byrne also created This Book Just Ate My Dog (2014) and This Book Just Stole My Cat (2019).

As the third in her series of Flora and Her Feathered Friends, Idle’s wordless plot this time was about jealousy when three friends were involved. To add implied motion to her two-dimensional illustrations, Idle incorporated flaps to lift that reveal other poses underneath. When a flap was lifted quickly up and down—similar to the way a flip book works—the pictures above and below simulated movement, animating the scene and making the lift-the-flap feature more than a mechanical but rather a fine addition to a story about dancing. Idle ended the book with a panorama as pages were flipped back in a gatefold to reveal the resolution to the three friends’ dilemma.

Just as Macaulay’s Rome Antics (1997) was a bird’s viewpoint of the famous city, this picture book was an experience from a worm’s eye perspective of the world. A little girl looked up from a wheelchair as she sat on her balcony, creating a dramatic, unexpected visual experience upward for the audience. A similar idea of changing perspectives is found in The Blanket Where Violet Sits (2022, Candlewick) by Allan Wolf, illustrated in pencil and digitally by Lauren Tobia.

2016 Jean Julien (French, 1983-), Author/Illustrator. This Is Not a Book, Phaidon

In a transformative tour-de-force of visual literacy, Julien created each turn of the page into a new metamorphosis. A double page spread was a pretend piano keyboard, or turn the book sideways and the bottom page was a laptop keyboard with the computer’s monitor on the top.

2017 Brian Biggs (American, 1968-), Illustrator. Noisy Night, written by Mac Barnett, Roaring Brook Press

A little boy heard sounds coming from the apartment above his bedroom, which were shown on the next page to come from an opera singer who, in turn, fretted about sounds coming from above his head, and so on for characters in subsequent apartments higher and higher. The split-level illustrations ingeniously showed across the top of each page just enough of each apartment above to hint who the occupant might be.

2018 Jon Agee (American, 1959-), Author/Illustrator. The Wall in the Middle of the Book, Dial

Not since Sendak placed a tree, then a sea monster, then another tree conspicuously near the gutter have illustrators like Agee deliberately and so successfully called attention to the gutter as an element in book design. Agee told the story of a young knight who convinced himself that his side of the book (the left page) was safe from a tiger, a rhino and an ogre that populated the other side (the right page) because a red brick wall ran smack down the gutter that separated them. Only when water was rising on the left side did the knight call for help from the right side, where a good guy happened to come to his rescue. Other picture books using the gutter as design element were Don’t Cross the Line! (2016, Gecko Press) by Isabel Minhos Martins, illustrated by Bernardo Carvalho, and This Book Just Ate My Dog (2014, Henry Holt) written and illustrated by Richard Byrne.

2018 Brian Selznick (American, 1951-), Author/Illustrator. David Serlin, Co-Author. Baby Monkey, Private Eye, Scholastic Press

This unique blend of picture book, easy reader chapter book and graphic novel was about Baby Monkey as he solved five cases. Each single-page drawing faced a simple sentence in large typeface on the opposite page. In contrast to detailed scenes were uncluttered images of Baby Monkey as he struggled to get on his pants. Alternating busy illustrations with bold, simple ones paced the story, a dramatic storytelling device that Selznick says he learned from his hero, author/illustrator Remy Charlip: “…the very act of turning the pages plays a pivotal role in telling the story. Each turn reveals something new in a way that builds on the image on the previous page.”

2019 Simon Bailly (French, n.d.). The Book in the Book in the Book, written by Julien Baer, Holiday House

A boy separated from his parents found a book about . . . a boy separated from his parents who found a book about . . . you guessed it, yet another. Topping it off was how the conceit was carried out, with a series of smaller books attached to the pages. The same idea with animal characters was found in Jesse Klausmeier’s Open This Little Book (2013) illustrated by Suzy Lee.

2019 Kevin Cornell (American, n.d.), Illustrator. Chapter Two is Missing! written by John Lieb, Razorbill

An exceptionally witty and inventive book in which the audience participated to help find a chapter that had been stolen, this was a sophisticated approach to the idea of what books are all about. It was a funny whodunit with some of the punctuation off-kilter, a bunch of letter Ms hiding in Chapter 5, and a Chapter 45 that does not even belong to the story. The Book With No Pictures (2014, Rocky Pond Books) by B. J. Novak is equally silly, since everything written on each page must be said aloud by the person reading it.

Lin used a snowy-white background for a bedtime story in which a child and his new feather bed appeared to float in the air. Lin’s vibrant gouache paintings of child, mother and bed appeared to jump off the pages—floating without a baseline on the negative space of the background— and Little Snow’s pajamas melded with the feathers bursting from his new bed that turned into snowflakes. Text placement was informal and perfectly shaped to fit within the field of action. A cameo appearance of Peter from Ezra Jack Keats’ 1963 Caldecott Medalist, The Snowy Day (1962) appeared at the window, just as the illustrator’s endpapers for 2019 Caldecott Honor Book, A Big Mooncake for Little Star (2018), were an homage to Robert McCloskey’s 1949 Caldecott Honor Book, Blueberries for Sal (1948), which “sums up the Americana she wanted to be a part of.”

2020 Beatrice Alemagna (Italian, 1973-), Author/Illustrator. Things That Go Away, Abrams

Alemagna is a superior oil painter with her childlike images. An innovative element of design was the use of vellum pages that cleverly showed the transformations described in the text.

Ordering Bibliography

Agee, Jon. The Wall in the Middle of the Book, 2018, Dial

Alemagna, Beatrice. Things That Go Away, 2020, Abrams

Baer, Julien. The Book in the Book in the Book, illustrated by Simon Bailly, 2019, Holiday House

Barnett, Mac. Chloe and the Lion, illustrated by Adam Rex, 2012, Little Brown

Barnett, Mac. Noisy Night, illustrated by Brian Biggs, 2017, Roaring Brook Press

Byrne, Richard. This Book Is Out of Control! 2016, Henry Holt

Duquennoy, Jacques. Little Ghost Party, 2013, Abrams

Gravett, Emily. The Rabbit Problem, paper engineering by Ania Mochlinska, 2009, Simon & Schuster

Idle, Molly. Flora and the Peacocks, 2016, Chronicle Books

Jin-Ho, Jung. Look Up! 2016, Holiday House

Julien, Jean. This Is Not a Book, 2016, Phaidon

Lieb, John. Chapter Two is Missing! illustrated by Kevin Cornell, 2019, Razorbill

Lin, Grace. A Big Bed for Little Snow, 2019, Little Brown

Macaulay, David. Black and White, 1990, Houghton Mifflin

Picard, Matthias. Jim Curious: A Voyage to the Heart of the Sea, 2014, Abrams

Selznick, Brian. The Invention of Hugo Cabret, 2007, Scholastic

Tan, Shaun. The Arrival, 2006, Arthur A. Levine

Torseter, Øyvind. The Hole, 2013, Enchanted Lion Books

Wiesner, David. The Three Pigs, 2001, Clarion Books

Willems, Mo. Knuffle Bunny: A Cautionary Tale, 2004, Hyperion

Wimmer, Sonja. The Word Collector, 2012, translator Jon Brokenbrow, Madrid: Cuento de Luz

Wood, Don. Into The Volcano, 2008, Blue Sky Press

Young, Cybèle. Out the Window, 2014, Groundwood Books

Note: This blog was created by Lyn Lacy to share history and express personal opinions about innovative picture books. Please respect copyrights of the images which are for educational purposes only and are not to be copied for any reason.