The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams:

Illustrator Erin E. Stead and Author Philip C. Stead into the 21st Century

Article 15

by Lyn Lacy 8000 words

Today’s children have interactive toys that talk back (sometimes in unique languages like “Furbish”), are adventuresome cowboy action figures in animated movies (“Toy Story” franchise), and are stuffed toy dinosaurs on PBS (“Barney and Friends” series). However, in the early 20th century, toys that could walk and talk were only found in Old World tales like “The Steadfast Tin Soldier” (1838, Hans Christian Andersen), “The Nutcracker” (1816, E. T. A. Hoffmann), Pinocchio (1883, Carlo Collodi) and the first of the Raggedy Ann Stories (1918) by Johnny Gruelle (1880-1938).

Then in 1922, The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams was published, a story not only about toys as sentient beings but also about how they became real. The novel is sad and sentimental, best known for its quote by the wise old Skin Horse in the nursery: "Real isn't how you are made... It's a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become real."

Margery Williams Bianco (1881—1944) was born and raised in England and moved to America with her family in 1890. She returned to London in 1901, married Francesco Bianco in 1904 and had two children, Cecco and Pamela, who was a child prodigy as a painter. The young family came back to the U.S. in 1921 and the next year The Velveteen Rabbit was released by George H. Doran in New York and William Heinemann in London. “’Throughout her life, Williams understood what it meant to be real,’ said her grandson, Mike Bianco. ‘She understood that all of these trappings of prestige and material possessions that we associate with being happy and what will endear us to others really fall short,’ he says, ‘because it's only when we allow ourselves to both give and receive unconditional love that we really become truly contented’” (Elizabeth Blair, “As ‘The Velveteen Rabbit’ turns 100, its message continues to resonate,” NPR, April 12, 2022).

Continuing through the 1920’s and 1930’s the author wrote over a dozen more children’s books and young adult novels, including a 1937 Newbery Honor Book award winner, Winterbound (1936) and two more about sentient toys, The Little Wooden Doll (1925) and The Skin Horse (1927), both illustrated by Pamela Bianco.

Illustrations for the original The Velveteen Rabbit were by Sir William Nicholson (1872-1949), an accomplished British painter, printmaker, illustrator and stage designer who also illustrated his own stories and works by Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Waugh and Siegfried Sassoon. Credited with elevating children’s book illustrations to a fine art, Nicholson’s seven original lithographs were handsome in their way for the time period, with tints and shades of magenta, cyan, brown and black. His figures were outlined in black, and the four single and three double page spreads within 33 pages were formally framed by a slender line separating them from margins of white space. The Doubleday 1991 edition did nothing to enhance Nicholson’s art by having endpapers covered with splotches of yellow messily dabbed across half-finished sketches of rabbits.

The book has never gone out of print and has been translated into dozens of languages; produced as live action, feature films and stage productions, including a musical. It has been produced as video narrated by Meryl Streep with illustrations by David Jorgensen, music by George Winston and filmed by my old friend Paul Gagne (the first gorgeous animation produced in 1985 by Rabbit Ears Entertainment). It has been reissued with illustrations by Maurice Sendak (1960), Michael Hague (1989), Charles Santore (2013) and now Erin Stead (2022).

For illustrations that were delicate and gentle, like the story itself, no choice in 2022 could have been better than the Caldecott Medal winner Erin Stead (1982-), who said in the same NPR article that she believes this classic story endures because its message applies to both children and grownups. “The notion of what's real carries with you for the rest of your life, with all of the relationships you have, all of the friendships that you'll make and all the times people aren't necessarily kind to you. There's a lot of insecurities. There's a lot of figuring out how you belong. It's hard to shake a story that's that honest."

Erin is as direct and sincere a visual storyteller as one can find. She always planned to be an illustrator at the beginning and end of her college years at the Maryland Institute College of Art and the School of Visual Arts in New York City, but for a period in between, painting was her artistic goal. "For a while I thought I would be a serious painter, the kind that smokes cigarettes and wears a black beret," she recalls. "But then I got back to illustrating. It keeps me honest, and I'm much happier doing it." After college, Stead worked at several bookstores and spent a year as assistant to the creative director at HarperCollins Children's Books.

She has also illustrated texts that are not the focus of this blog post, yet they are significant in the development of Erin’s art. For poetic texts by Julie Fogliano, And Then It’s Spring (2012, runner up for the 2012 Boston Globe-Horn Book Award) and Fogliano’s If You Want To See A Whale (2013), Erin’s placement of the horizon line toward the top of pages controls attention to activities in a garden and the sea below. In Tony (2017) by Ed Galing, the eye is constantly on the gentle, patient old draft horse and its wagon. She also illustrated a tender story about the most engaging of characters in The Uncorker of Ocean Bottles (2016) by Michelle Cuevas.

Erin’s favorite illustrators are Maurice Sendak and recently, Sebastian Meschenmoser (1980-), one of Germany’s most successful and admired young illustrators for children. The only artist from whom she has said she took inspiration was Evaline Ness, whose work she studied "to get to how I wanted to think about color in my drawings." (Rachel Steinberg, “Spring 2010 Flying Starts: Erin Stead”, Publishers Weekly, June 28, 2010.)

As The New Yorker columnist Sarah Larson described the Steads’ relationship with their editor Neal Porter, Erin once worked with a group of other talented young friends at the renowned Manhattan children’s bookstore Books of Wonder. The story goes that the first one in the bookstore group to be published by the prestigious editorial director Porter and his award-winning imprint at Roaring Brooks Press (now at Holiday House) was Nick Bruel (1978-), then George O’Connor (1973-) who then passed along Philip’s work, who then showed Porter a sketch by Erin, who then sent Porter poetry by Fogliano. Porter called the group his “Books of Wonder mafia,” and most of the Steads’ picture books below have been with his imprint (Sarah Larson, “The Making of a Quiet Children’s Classic,” The New Yorker, March 15, 2017).

Philip (1982-) wanted to be an artist since elementary school when his favorite illustrator was Quentin Blake. He and Erin became friends when they sat next to each other in high school art class in Dearborn, Michigan. They soon found out they shared an interest in illustrating children’s books. The high school art teacher Mr. Foley was the one who showed Philip a pamphlet featuring Sendak’s steps for creation of Where the Wild Things Are, and Philip began to experiment with the duel challenges of creating a sequence of pictures as opposed to a single canvas and portraying characters in a variety of ways throughout the pages. He continued to study art at the University of Michigan.

Philip is well-known for his whimsical, ingenious mixed-media illustrations with their delicate and colorful palettes for his own texts in Creamed Tuna Fish and Peas on Toast (2009); Jonathan and the Big Blue Boat (collage, 2011); A Home for Bird (crayons, 2012); Hello, My Name Is Ruby (chalk pastels and ink, 2013); Sebastian and the Balloon (2014); Samson in the Snow (2016); Ideas Are All Around (various media, 2016); All the Animals Where I Live (2018); Vernon Is on His Way: Small Stories (2018); and I'd Like to Be the Window for a Wise Old Dog (2022). He also illustrated In My Garden (2010), originally published in 1960 by Charlotte Zolotow and wrote Special Delivery (2015); The Only Fish in the Sea (2017); Follow That Frog! (2021); and Every Dog in the Neighborhood (2022), all four of which his friend Matthew Cordell (1975-) illustrated.

After their marriage in 2005, the Steads first lived in Brooklyn, now in an old farmhouse with daughter in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and work together in their studio, a renovated 100-year-old barn. They have a common workspace as well as their own work stations, a pin-up wall for ideas, a cushy bed for dog Wednesday who has been present for every book they’ve made, a flat file for finished and unfinished books and a horseshoe over the door for luck. “Music sets the tone for the day,” said Erin, and inspiration as well as practical information is found in their library in the loft (“Tour Philip and Erin Stead’s Michigan Studio,” YouTube, “Random House Kids,” November 7, 2017).

Philip admitted they have wanted to be like the famous married illustrators, Alice Provensen (1918-2018) and Martin Provensen (1916-1987). "I often wonder how people do this without someone with them in the studio all the time," he has said. "We're constantly passing things back and forth to each other." Erin agreed: "There are actually moments when you can see us copying each other, sometimes on paper, sometimes not. Sometimes you're just sitting at your desk, and no matter what, you just can't draw a character design," she concluded, citing Amos McGee's rhinoceros, which her husband helped her get started on. (Rachel Steinberg, “Spring 2010 Flying Starts: Erin Stead”, Publishers Weekly, June 28, 2010.)

Working together, Erin and Philip have found many ways to stretch their talents in exciting directions. They work on more than one idea at a time, since they say writing, illustrating and designing are not usually perfect from the beginning so require time and patience. Very important to both of them is the design of each book, including size, cover, endpapers and front matter, and they make decisions with such designers as Jennifer Browne and Jen Keenan at Roaring Brook and Martha Rago at Doubleday. First, a review of Erin’s illustrations for a 100th Anniversary Edition of The Velveteen Rabbit. Always rewarding is to hear from an illustrator about intentions with a book, so Erin’s own words are welcomed additions to this post.

2022 The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams

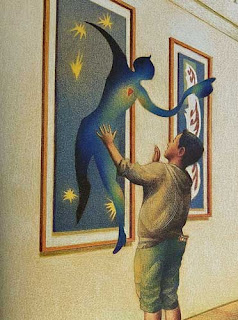

For many reasons, Erin was an ideal illustrator to reimagine The Velveteen Rabbit. For one thing, she wanted her edition to appeal to adults as well as children. “Because it has been re-illustrated so many times, I wanted to do something that felt a little new. I wanted the illustrations to feel timeless but a little modern, maybe a little bit more grown up. The book isn’t just for children. It’s something a grown-up could give a grown-up.” She continued elsewhere, “I was hoping to make an edition that an adult would read and give to their friends, particularly after the last few years we’ve all had. I hoped this edition would look grown-up enough to be taken seriously — that it looked like it respected the reader, whether they are eight or 80 years old” (Joanne O’Sullivan, “First Look: Erin Stead’s The Velveteen Rabbit for Its Centenary,” Publishers Weekly, December 16, 2021).

Another reason is that Erin also envisioned her own design for the book, one that considered placement of text and illustrations to best move the story along. She included an elegant and perceptive illustration as each of the 39 pages was turned. “Both Phil and Martha Rago helped me with the book design…Although I am somewhat versed in book design, Phil actually went to school for it and continues to be more proficient at the nitty gritty of it all…I had some pretty specific ideas going into the book…I am very possessive about layout and pacing. It’s one of my favorite parts about storytelling…I was hoping by designing the type and layout the way we did, that people would sit down and read the story. It’s a storybook, not necessarily a picture book” ((Julie Danielson, sevenimpossiblethings, May 12, 2022).

“The original edition was limited by the confines of the technology of its time period, a printing press fitted with lead type, leaving no flexibility as to how the text could be laid out on the page. With the centenary edition, she said, ‘I was able to do things they wouldn’t have been able to do. That began with breaking up the text to reflect the way the pages should be turned, where I wanted pauses,’ all with the aim of presenting the story ‘in the way we actually read to kids’” (O’Sullivan).

One satisfying result of this meticulous planning was that each of the three wordless double page spreads was placed for emotional effect at a vital point in the plot, encouraging the audience to pause and reflect on the lengthy texts from preceding pages—dialogues with the Skin Horse, with the doctor and with the real rabbits. “I illustrated a pause right after that last devastatingly awkward moment, where we spend a full spread in the woods with the Boy taking him home. I enjoyed drawing that moment out of the text and forcing the reader to pause there” (Danielson). Another equally successful book design was four single page portraits of the Rabbit himself for the audience to witness subtle changes in him as the story unfolds—or catch the surprising similarities in his “knowing expression” before and after becoming “Real to everyone.”

A third reason is that Erin’s artistic style made her a perfect choice for a story from the early 20th century. She is known for soft figures in muted tints, created by intricate workmanship using woodblock printing and her signature mastery of colored pencils. Examples of her delicate touch were the underlying hues on three wordless double page spreads that indicate the seasons and add skillfully to pacing in the story—wintertime (muted purple), spring/summer (yellow and green) and autumn (rusty red).

She had previous experience drawing rabbits (2012, And Then It’s Spring) and a horse (2017, Tony) and in The Velveteen Rabbit, she illustrated with elegant precision a child’s 19th century riding horse on wheels, as well as a toy Rabbit stuffed with sawdust covered in velveteen and sateen. “The resulting illustrations showcase Stead’s gift for animating the characters of the story. ‘She really makes a connection,’ said Frances Gilbert, editor-in-chief of Doubleday Books for Young Readers. ‘Her animals reach out and grab readers.’ The rabbit’s cocked ear, the empathetic stance of the Skin Horse as he counsels the bunny offer a fresh and endearing vision of these iconic figures” O’Sullivan).

As for other characters in the text, Erin said, “I love how the humans really aren’t that important. The boy is kind of important… But the highs and lows in the story tend to come when the Rabbit is without the boy…(Williams) grabs you by knowing you probably had your own version of the Velveteen Rabbit. That’s what Williams is talking to you about” (Danielson).

In the same interview, Erin explained her choice not to illustrate the nursery magic Fairy. “When I’m illustrating for a slightly older audience, sometimes I make the decision to back out of the room and let the reader decide what this part of the story looks like. I am not a caricature-type illustrator. I tend to get too detailed in portraiture. Sometimes I think this aids the story, and sometimes I think this would get in a child’s way. For this fairy, who is a kind hero, I want them to look however the reader might imagine them. The author provides a good deal of description in the writing.”

Erin Stead combined her gentle artistic touch, superb eye for page/book design and astute recognition of the story’s ageless qualities with an empathetic read of the author’s intent to create a truly welcomed addition to this iconic story from a hundred years ago.

(On a personal note: There are no rabbits in my back yard, only the occasional bird in the birdbath and the neighborhood’s cats. But I like to think that rabbits would enjoy a dance among the forsythia, including a velveteen rabbit made real by a nursery magic fairy. No matter how old I am, no matter where I’ve lived, I have held such thoughts since my mother read the book to me at age four. She was strict and she was stern and she brooked no nonsense from anyone, so why would she have listened to my little girl’s pleas to read such a sentimental book again and again? The book was from her childhood in the 1920s as well as from mine in the 1940s, so just perhaps she too had listened to it being read aloud and just maybe asked for it again, and it could just be that she once as a child believed as I still do as an adult. She never said, and I’ll never know. As I sit with these thoughts, a helicopter startles me as it circles above out of the blue. My husband comes to the kitchen door and yells over the noise, “TV says it’s police searching for a carjacker on foot in our neighborhood. Come in before they think you’re him.” He disappears into the house. My husband was once a police reporter. I’m laughing at what this silly old man I love said as I get up to do what he tells me to do. “Sounds like something Momma would’ve said,” I say only to myself, “but you know, it could just as well be a fairy overhead looking for a rabbit.” I go in, I never say, and we’ll never know. LL)

The Steads have collaborated on six books reviewed below (another to come out in November), each an exceptional achievement with its innovation, humor and long-lasting appeal. They epitomize wit, poignancy and wisdom with each book. As they pursue their inventive and engaging careers, they leave no doubt that they are one of the most innovative teams creating picture books into the 21st century.

2010 A Sick Day for Amos McGee

2021 Amos McGee Misses the Bus

Philip Stead wrote A Sick Day for Amos McGee knowing it would be perfect for Erin to illustrate—even before she knew it herself. "Before this book, I don't think I ever actually sat down with the intention of writing a story," he says. But with Amos McGee, "I sat down at my desk and thought I'd write a story for Erin. I thought of characters specifically for her."

From Erin's perspective, events came as more of a surprise. "Neal (Porter, Roaring Brooks Press) and Phil took me to dinner—I was unaware of the story at the time—and they both asked if I'd illustrate it. I just fell into it." Amos McGee became A Neal Porter Book and was named one of the "10 Best Illustrated Children's Books" for 2010 by The New York Times before it won the Caldecott Medal in January 2011.

The Steads’ Medalist is a gentle, heartwarming lapbook that is a good read for any sick youngster who ever stayed home from school. Erin said in her Caldecott Acceptance Speech that the little book “is about having good and loyal friends.” These friends were softly washed in tints of blue, pink or green (accomplished with wood block printing), while other things might be supple line drawings on the same pages. Such simple drawings in uncomplicated, familiar scenes can often be the most satisfying picture book art for the very young.

Erin’s talent with her pencil resulted in illustrations that invited closer scrutiny for little things Philip never mentioned. For instance, nowhere did the text state that Amos McGee was old. Yet, there he was, an octogenarian, getting ready for work with sweet smiles of utter contentment that the illustrator never changed (except when he had a pinkish nose from sneezing). Erin made a little clay model or maquette of Amos to study him from different directions and manipulate him into different positions.

Amos also did not live alone; a mouse and a toy bear were shown to keep him company. Illustrations that followed revealed even more details: Amos’ little house was squeezed between two high-rises…at the end of his ride on the Number 5 bus, a red balloon had drifted out the door of the bus into the Zoo…the balloon was seen on the title page and later in the story tagging along with an elephant, a rhino, a tortoise, a penguin, an owl and the tiniest of birds leaving through the Zoo’s gate to find out what had happened to their friend.

Two wordless double page spreads were In the exact middle of the book (considered to be a privileged spread), showing the animals waiting for the bus and then sitting inside it (the bird was on top) behind the bus driver, whose unperturbed expression gave the impression these friends might have pulled off such a well-intentioned, well-mannered and well-executed escape before.

The second half of the story had such enlightening details as well. At Amos’ house, the only scene funnier than the elephant holding playing cards (on the cover) was Amos himself beneath his blanket playing hide-and-seek with the tortoise. He didn’t have on his bunny slippers and had some of the best toes ever drawn. On the wordless last single page, the only detail dearer than Amos sharing his blanket with the rhino was the red balloon flying freely in the night sky outside the window.

“Asked what she'd like people to take away from Amos McGee, Erin has a ready answer. ‘It's up to the readers,’ she says firmly. ‘I want them to have their own experiences with it. Because I have mine’" ((Rachel Steinberg, “Spring 2010 Flying Starts: Erin Stead”, Publishers Weekly, June 28, 2010).

In Amos McGee Misses the Bus (2021), the Steads teamed up again with the same brief text and soft artistic style about Amos, who stayed up all night this time planning an outing for his friends, missed the morning bus and was thus late for work. His little roommate, the mouse, and a tiny bird discovered that in his haste to catch the Number 5 Amos had run off without his lunch pail and then lost his favorite hat. (He had also neglected to bring a ubiquitous beach ball.) The mouse held up signs that say “Wait!” and “Hold On!” but warnings by the bird were three exclamation points over his head.

As Philip explained in an interview, “Notice the little mouse is there, foretelling, from the first page. The world right now is so loud and meaner and less kind, so we wanted the world of Amos to be a step back to all the reasons people loved the first book” (Martha Marani, The Ivy Bookshop, virtual interview, Kids’ Writers Live!).

Poor Amos had to walk to work with only the beach umbrellas and an attractive embroidered tote bag, even though “There will be no time for an outing today.” However, while sleep-deprived Amos dozed on a park bench, the zoo animals finished his chores so now there was time to catch the afternoon Number 5 and go on their outing to the beach after all. The End. A perfect little wrapped-up, happy-ending story.

“Wait!” “Hold On!” !!!

What could Philip and Erin do together to make life for Amos even better?! As it turned out, in the middle of the book the tortoise stepped out the zoo gates for a bit of exercise and fortuitously met up with Amos’s mouse and bird. In a sequence of pages (including our audience’s favorite, a horizontal fold-out panorama that extended his journey), the tortoise brought Amos his lunch pail and favorite hat (plus the beach ball was retrieved by the zoo’s monkey). The group of friends headed for the beach, and now that was a perfect ending. “The tortoise is a background character,” Philip explained, “the devoted one who gets the job done” (Marani).

As the Steads well know, their books are about the details. Every word in Philip’s short text matters, and every spread by Erin moves the story along. For instance, illustrations were again set firmly on a horizontal baseline, such as the sidewalk or hedgerow that led the eye from left to right and on to the next page. Occasionally, a drawn line had unobtrusive little curlicues at each end, right and left, as if to draw attention to the beauty of the underlying linear structure itself. The two double page spreads of everyone lined to catch the Number 5 and then riding inside were welcomed repetition from the first book, with the addition of Amos himself sitting this time behind an unfazed female bus driver.

Adding to earlier praise of Erin’s ability to draw some of the best toes ever is now her amusing inclusion of another pair of shoes to Amos’s wardrobe. In A Sick Day he had his bunny slippers, boots, waders and sneakers, and in Misses the Bus he also sported a pair of Grecian sandals for the beach. He wore them with socks, as us older folks are wont to do, and he topped things off nicely with shorts, shades and beach chair.

A man for all seasons was our Amos McGee.

2012 Bear Has a Story to Tell

The weight of meaning and relevance have by now been layered onto Bear Has a Story to Tell by enthusiastic reviewers who wax far more elegantly than this blogger. For instance, a Publishers Weekly reviewer pointed out, ”Helpfulness in picture books can teach a moral lesson or it can let readers imagine luxuriating in that tender care themselves.” And when Bear forgot his story, “The quiet suggestion that no one has all the answers is just one of the many pleasures the Steads give readers” (Emily van Beek, Folio Literary Management, Sept 2012). When the book was cited as a Kirkus Reviews Best Children's Book of 2012, the indie reviewers wrote such praiseworthy phrases as ”the Steads’ work adopts a folkloric approach to cooperative relationships"; “animals that stand in for humans convey a nurturing respect for child readers”; and “it explores a second, internal theme: the nature of the storytelling narrative itself: when Bear can’t remember his story, his friends suggest a protagonist (‘Maybe your story is about a bear’), a plot (‘Maybe your story is about the busy time just before winter’), and supporting characters (themselves).”

All of this and more may certainly be true about the intent behind Philip’s text, for he is a seriously conscientious storyteller with deep respect for creatures of this world and what children might learn from them. However, he also has a sense of humor and a light touch and might be the first to agree that he was crafting a deceptively straightforward tale in the classic tradition of three characteristics for a “predictable story” in children’s literature. (1) A simple repetitive pattern involved a walk through the woods, a series of woodland friends and Bear’s question, “Would you like to hear a story?” (2) A cumulative sequence was Bear asking each friend and getting similar negative responses. (3) A circular structure resulted in the last page ending with the same line from the first page, “It was almost winter and Bear was getting sleepy.”

Perfection in these classic traditions, Philip, pure and clean, and children love it. Enough said. Except to add thanks to you and Erin both—nothing could be funnier than a bear patting down leaves and pine needles over a frog. And nothing could be more respectful of an audience than simply stopping the text with, “The first winter snowflakes began to fall” so that a single wordless spread could show what did not need to be said— bears hibernate in winter. Just as you both also show in the front matter leaves falling before the first line of text that tells that winter is coming.

Erin’s illustrations picked up so much of what Philip’s text left out that it’s no surprise if these two sometimes must literally add to each other’s thoughts. Erin’s Bear was the lumpy, waddling, snowflake-gazing kind of bear that leaned, stretched, yawned, scratched absent-mindedly and was easily distracted by needs of his friends. She let us know from the beginning that Bear, sweet old dear, was not the kind of bear to remember that story of his. We adored his scruffy coat and big belly, and watched with affection as he tenderly took care of those so much smaller than he is.

Publishers Weekly reviewer said it best, “Erin’s bear is especially soulful. It might be the way his eyebrows furrow with concern, or the way he leans forward to hear what his friends are saying.” And the Kirkus online reviewer (April 25, 2012) pointed out, “Sharing an affinity with Jerry Pinkney yet evoking the sparer 1960s work of Evaline Ness and Nonny Hogrogian, Stead’s compositions exude an ineffable, less-is-more charm” (High praise to this blogger, since Pinkney, Ness and Hogrogian are also three personal favorites over the years.)

Bear Has a Story to Tell is his story for Philip and Erin to show and tell, also available as a board book, a CD and a streaming 9-minute video with limited animation by Weston Woods/Scholastic.

2015 Lenny & Lucy

The most creative amongst us might want to stuff and sew our own big friends like Peter’s creations of Lenny and Lucy, but a serious doubt exists that anyone could do so successfully. Not to say Phillip had not given good instructions—for Lenny, Guardian of the Bridge, “take a pile of pillows…find just the right blankets…stitch and sew and wrap the pile up, trying it shut with string…push and pull and knead the wrapped-up pillows like dough.” For Lucy, good friend to Lenny, “gather all the leaves on the ground and make a tall pile…find just the right blankets…push and pull and knead the wrapped-up leaves like dough.”

Then Erin goes on to present the two absolutely squishy, roly-poly funsters straight out of cartoon heaven, eager to become a part of children’s lives. Even if Lenny and Lucy were to be created by the most creative amongst us, the serious doubt remains that they could enjoy toast and jam and a glass of milk, play marbles, eat vegetable soup, stand upright and tip a hat, look through binoculars for owls or chase after a squirrel or two. Or that they, like Lenny and Lucy, could keep watch all night so that the terrible idea of terrible things “they couldn’t see…hiding in trees” in the woods would not come across the wooden bridge, which is why neither Peter nor Harold had been able to sleep at all.”

Only Philip’s and Erin’s extraordinary talents could create such wildly imaginative characters, who come to life in words and pictures to delight us all with their charming demeanor, spontaneous friendship and heartfelt promise of a good night’s rest. Not since Sendak’s Wild Things have big funny-looking friends like these shown a kid a good time when life turned dreary.

And some amongst us might also want that exuberantly flowered wallpaper in Peter’s room, but a serious doubt is that such exists except in Erin’s astute ability to fill double page spreads with such a comforting flower garden as emotional contrast for children to the dark unfriendly leafless woods out the window, across the bridge, over there in the unknown.

Although Lenny, Lucy and Harold—“who was only a dog and couldn’t do much about it (even though he wanted to); Harold was a good dog”—were helping Peter get through the anxiety of facing life in a new home, truly saving the day and fears in the night was neighbor Millie as a new buddy with her bag of marshmallows and binoculars to search for interesting things like owls (which Erin had already shown the audience, sans binoculars).

Philip’s book design featured endpapers of a vibrant red orange, a color traditionally chosen to represent excitement and happy times. However, front matter followed of gold and grey pages painted by Erin and indicated her more somber attitude to come, expressed throughout the story by her continued use of grey with only accents of gold and other subdued hues, all accomplished by flawless carbon transfer printing, egg tempera and charcoal.

When Millie arrived however, she was dressed in red, a most cheerful color on a timid little girl standing slightly apprehensive with her feet crossed. Once again, Erin showed her love of posing feet in such a manner as to add to a character’s attitude or personality, as she had with similar postures in her other books—dangling feet, curled toes on a cold bare floor, curled-under toes in socks, hopping legs on a chicken, dancing rabbits’ hind legs, a horse’s dancing hooves, tiptoes, pigeon-toes or “out-toes,” a soldier’s marching boots, splay-footedness, elegantly crossed legs with a foot turned up, on and on. All such fun to find.

Returning to engaging details of color, Millie’s mother’s shirt also had a red stripe, and red was the color of the door on their house as well, which the artist showed at the end when two houses, two cars, two upstairs flashlights and the two Guardians are shown protecting two kids on their safe side of the bridge. The same vibrant red orange back endpapers punctuated just such a happy conclusion. All in all, this book is one of the most sophisticated examples of the Steads’ inventive uses of color in art and design.

Philip has said he admires Sendak’s last page in Where the Wild Things Are—that succinct five-word postscript “and it was still hot” which was considered a bit startling by critics in its day. In Lenny and Lucy, once Peter’s terrible ideas about terrible things in the woods had been kept on the other side of the bridge, Philip paid homage to Wild Things with his own denouement—“where they belonged.”

2017 The Purloining of Prince Oleomargarine

A challenge for Erin in illustrating Purloining was probably stifling giggles long enough to get images on paper after first reading Philip’s outrageous text. And Philip might well have looked over her shoulder—grinning like a gleeful kid—at her illustrations before wandering off to do whatever he did for the rest of the day. Who else but Philip would write about a bearded character who “smiled the way certain men smile after winning something at someone else’s expense,” even though nothing else was seen of the guy in the entire book. Perhaps Erin had asked Philip to work him in because she had a desire to draw just such an expression.

This reviewer has not just looked at but also read every word of this delightful book from cover to cover a couple of times—no no, as Mark Twain himself might admonish this blogger severely, one needs to See rather than merely Look At, so said Jack Debes (1914-1986) of Eastman Kodak in Rochester, NY, when he defined “visual literacy” (see Appendix A below for Jack’s full definition). “Visuals are a language,” is another Jackism that Twain would have liked as much as we do.

To continue with discussing the brilliant writing and illustrating of Purloining (in case readers are getting bored with digressions): according to Philip, he sat down a few years ago with Twain on Beaver Island in Lake Michigan to flesh out Twain’s rough notes for an unfinished story over a hundred years ago for his daughters. The two storytellers were not always in agreement, as when Twain would remark that Philip’s “version lacks credibility” or a disgruntled Philip would complain his “mind began to drift.” Encapsulating their subsequent collaboration here does a dire injustice to Philip’s tour de force of the fairy tale genre. However, in the best of author-illustrator companionships, Philip and Erin combined their innovative talents to extend Twain’s notes into a 150-page illustrated storybook that was funny as well as smart in its portrayal of wit, poignancy and wisdom through words and pictures.

Foremost in the story was Our Hero Johnny, a simple boy who “chose to carry a moral compass” even though he was poorly clothed and always hungry. His sidekick was a chicken named Pestilence and Famine, a joy to watch hopping on one leg—“thinking it was the thing to do” after observing Johnny hopping around when he stubbed his toe. Next was Johnny’s mean grandfather, a bad man who flew into a rage, lay down and died, since the gods decided not to “add misery to the lives of the miserable.” (This “relentless gloom” from Twain had begun to bore Philip, but not this audience of children and me who cheered, Hurrah! RIP! Good Riddance to that dreadful man, whose dead boots are the only things Erin showed us.)

Reading Philip’s prose as well as Erin’s illustrations up to this point gave clues surrounding the grandfather’s demise—backing up some pages, the audience saw that in order to sell Pestilence and Famine for food, Johnny had been sent three days to market, where the audience witnessed Erin’s hilarious parade of slumped-over villagers with “trumpets and drums and far too many cymbals.” (Being slumped over was by decree of the king, who was a jealous short fellow who had decreed those “exceeding his elevation” were “enemies of the state.”) Depiction of this parade was one of several, strategically-place wordless or nearly-wordless fully-populated double page spreads by Erin, and the giggles it elicited from the audience of children were noticeably raucous (we were so cautioned by a nervous librarian).

Erin’s beginning of the long procession actually began on the previous page and since the king had proclaimed only children and animals were allowed to stand upright, the soldiers on horseback, clowns on bicycles and band members with their instruments were hunkered over “as if they’d dropped something very small and very important in the road.” The parade’s end was pictured on the next double page spread as Johnny finally arrived at the otherwise peaceful market. With pennants flying and the king’s castle on a hill in the distance, the illustrator quietly oriented the audience in an Iconic Fairy Tale Land.

Philip’s and Twain’s pace slowed down, so Erin likewise rendered delicate single page portraits large and small and a tender sequence pictured at the bottom of four pages as Johnny encounters a beautiful-small-kind-old-blind-woman who takes Pestilence and Famine in exchange for a handful of blue seeds (seeds rather than food, which is the cause of the mean grandfather’s previously-mentioned raging, lying down and dying, poof!). Erin’s page designs using abundant white space and placement of figures sometimes in the corner of an otherwise “empty” page are exceptionally attractive and ingeniously provide just the right amount of pacing for this storybook.

Back home, Johnny planted one blue seed that grew into A Magic Juju Blossom which Johnny ate and then, true to fairy tale tradition, he could Talk With The Animals—every child’s dream come true. And sure enough, all the Talking Animals the audience could ever want built Johnny a Home in the Meadow and gathered for A Feast of Berries and whatnot—for the elephant to the jackrabbit, including Susy the helpful skunk, but not the tiger, who the audience was forewarned had “a different kind of tooth.” In gratitude, Johnny’s simple, truly-meant speech was, “I am glad to be here,” and all the creatures cheered over these “words that could save mankind from all its troubles, if only mankind could say them once in a while and make them truly meant.”

Erin had introduced the animals in a single left page illustration before Philip mentioned their arrival in his text, and the effect of seeing them first was one of awe and admiration over this unheralded surprise in the story. (Although Philip is prodigiously talented in illustrating animals, he has said no one loves drawing them more and is better at it than Erin.) Erin continued to focus her attention on the animals in individual portraits as well as in two more splendid double page spreads. Each one in the menagerie was rendered sensitively by the artist’s diaphanous touch with a pencil, urging the audience to linger for details of their gentle demeanors and comfortable interconnectedness. Philip then accentuated Erin’s respectful approach to this part of the story with words in a lovely song by the nightingale and a powerful speech by the lion. To say this was the heart of the book is an understatement.

Then, Twain had to butt in. Believing that “nothing is more boring than a barrage of good cheer,” he “stopped the story and skipped ahead to a suggestion of future peril”—the king was in a tizzy fit because his son Prince Oleomargarine was missing, who His Majesty said “is like Me in every way. That is to say—perfect…and he has immaculate teeth.” Our Hero brought in the Talking Animals to give evidence about the “PURRRRR-LOYYYYY-NINNNG “of the Prince (“Stolen,” explained the normal 5’7” queen), then Johnny and his friends set out on their Quest to bring the Prince home.

The text about the animals giving evidence was Twain and Philip at their silliest having fun with the “bumfuzzlement inside the hollow sitting room of the little king’s noggin.” Erin’s double page illustrations for this section were for the first time structured on strong vertical lines, emphasizing heights of stairways, tapestries, thrones and the animals themselves compared to His Majesty Not, His Highness Certainly Not, His Icky Rudeness. The queen however was beautiful, kind, decent, warm, empathetic, compassionate, knitting—oh, give us a queen any day, cried the audience of children, Purloining needs a sequel about the scarf she gave Johnny!

Again Twain was true to eccentric form, this time disappearing poof! without an ending for his story. Philip fell back on Fairy Tales 101 (sly author that he is) to introduce Two Ornery Dragons at the Entrance to a Cave, but he had apparently been with Twain the cynic too long and was not one to provide Our Hero Johnny with any Heroism. Instead, Philip brought in Susy The Helpful Skunk to frighten off the dragons with the potential of her smelly spray and even Pestilence and Famine returned, after all this time gone, and she and Johnny began to hop on one leg “thinking it was the thing to do” (Wha? So much for the menacing dragon fairy tale tradition.)

Inside the Cave, tall villagers had been hiding from the unreasonable short king, who considered them “giants, scourge of the nation.” To make their lives even more miserable, the brat Prince Oleomargarine had arrived with his immaculate teeth and bad attitude. However, who should slink in but the tiger who tricked the Prince into climbing on his back for a ride home ((remember, he had that different tooth? The silly kid fell for it. This the audience liked.)

What became of the tall villagers? Did Our Hero, a friendly but potentially-smelly skunk named Susy, a hopping chicken and the other animals hate them and reveal their hiding place for the king’s reward? None of it. In Philip’s and Johnny’s Fairy Tale Land, “all the money you can ever find will not afford you even one of the most important things around, which is: A true friend.” So, in a reprise of Johnny’s scene with the animals, he again said “words that could save mankind from all its silly, ceaseless violence, if only mankind could say them once in a while and make them truly meant.” “I am glad to know you,” was his simple, truly-meant response to the tall villagers. “And the giants wept.”

Philip’s wise, truly-meant text was accompanied at the end by a stroke of—can it be said?—ok, Genius. Earlier in the book and even printed on the cover (go look for it yourselves, the audience of children is told by me), Philip had quoted Twain: “I tell you this, there are more chickens than a man can know in this world, but an unprovoked kindness is the rarest of birds.” Jump back now to the end of the story, and befitting such a finely-honed tale was Erin’s small vignette in the corner of all that empty white space in which helpful Susy skunk sits with the beautiful-small-kind-old-blind woman, now with her fairy’s wings, both of them the rarest of birds.

This was followed by an Epilogue portrait of Pestilence and Famine, who Philip insisted lived to be a hundred, news that tickled the audience very much indeed.

Appendix A: “ Visual literacy refers to a group of vision competencies a human being can develop by seeing and at the same time having and integrating other sensory experiences. The development of these competencies is fundamental to normal human learning. When developed, they enable a visually literate person to discriminate and interpret the visible actions, objects, and/or symbols, natural or man-made, that he encounters in his environment. Through the creative use of these competencies, he is able to communicate with others. Through the appreciative use of these competencies, he is able to comprehend and enjoy the masterworks of visual communication” (Jack Debes, The Loom of Visual Literacy, c1969).

2019 Music for Mister Moon

Philip’s text said that Harriet Henry effortlessly changed her name to Hank, transformed her parents into penguins and turned her room into a cozy little house. She could not, however, make her regret over throwing her teacup become a new teacup. Erin’s illustrations showed that Hank could also make a bear be a hatmaker and a walrus become a fisherman, inspired by her stuffed toys sitting on a chair at home (with apologies to Philip and Erin, this reviewer has outlined the embossed image of them on the cover above so the reader does not miss them). However, the little girl’s hands still became sweaty and her face still became hot when she thought of playing her cello in front of others. Could she change her stage fright if she played before an audience of only one?

Describing and picturing how a child might get over the way she feels about something has been one tricky challenge for other picture book makers, but the Steads are well-practiced in demonstrating how their magical storytelling can often get a job done. Truly inspired was to have Hank spend an evening getting to know Mister Moon, no better character than that universal, constant, benevolent face up above as an audience for a first concert.

How it came about was so logically laid out by Philip and Erin that the audience fell right into suspension of disbelief. An owl interrupted Hank’s cello practice in front of her stuffed toys (so stands to reason she would throw her teacup out the window at him); teacup accidentally hit the moon, who fell and plugged up Hank’s chimney (so she made herself a ladder to get him down, easy peasy); Mister Moon said he gets chilly (off to the hatmaker) and “just once I’d like to float on the lake for real” rather than just watch his reflection (off to the fisherman for a boat). When the time came for the moon to go home, Hank was back to the fisherman (stands to reason she would require a net), back to the hatmaker (of course she herself would also need a hat) and back to the owl (everyone knows only an owl could collect other owls).

At the mention of Hank playing her cello for the moon, however, she gets sweaty hands and hot face. So, with a promise not to watch or cheer and in a marvelously inventive manner—shown only by Erin in a double page spread—the moon was hoisted back into the sky for an uninhibited solo performance.

Children with vivid imaginations like Philip’s Hank, who can make up things like a really tall ladder and offhandedly chat with an owl on a tree swing, can likewise sometimes wind themselves up by imagining terrible outcomes in unknown situations (see Peter in Lenny and Lucy). Adults recognize that such feelings of inadequacy and attitudes of resistance can be very difficult for children to get over, and parents Philip and Erin have done nothing less than present a lovely allegory for tackling such a challenge gently, thoughtfully, patiently, with humor and an absence of didacticism.

Comfortably couched in the Steads’ familiar theme of friendship, this original story about a little girl and her deepest fear is the collaborators’ most powerful book with a message so far. And the audience loved seeing a penguin, owl and bear show up from their other books again.

2022 The Sun Is Late and So Is The Farmer

“A mule, A milk cow, A miniature horse, Standing in a barn door, Waiting for the sun to rise. As this trio rests in their comfortable barn, a realization slowly dawns on them. . . the sun is late to rise. After consulting barn owl (who always knows what to do), they take Rooster and set off on an epic journey further than they’ve ever gone before; through the acre of tall corn, past the sleeping giant, all the way to the edge of the world.”mDue for release November 8. This blogger hopes to add a review here. (Echoes of a folk tale?)

The Steads' stories are all about acts of “unprovoked kindness.”

Ordering Bibliography

Stead, Philip C. Amos McGee Misses the Bus. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead. 2021. Roaring Brook Press. ISBN-10:1250213223, ISBN-13:978-1250213228

Stead, Philip C. Bear Has a Story to Tell. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead. 2012. A Neal Porter Book/Roaring Brook Press. ISBN-10:1596437456, ISBN-13:978-1596437456

Stead, Philip C. Lenny & Lucy. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead. 2015. A Neal Porter Book/Roaring Brook Press. ISBN-10:1596439327, ISBN-13:978-1596439320

Stead, Philip C. Music for Mister Moon. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead. 2019. Neal Porter Books/Holiday House. ISBN-10:0823441601, ISBN-13:978-0823441600

Stead, Philip C. A Sick Day for Amos McGee. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead. 2010. A Neal Porter Book/Roaring Brook Press. ISBN-10:1596434023, ISBN-13:978-1596434028

Stead, Philip C. The Sun Is Late and So Is The Farmer. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead. Due November 8, 2022. A Neal Porter Book/Holiday House. ISBN-10:0823444287, ISBN-13:978-0823444281

Twain, Mark and Philip C. Stead. The Purloining of Prince Oleomargarine. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead. 2017. Doubleday Books for Young Readers. ISBN-10:0593303822, ISBN-13:978-0593303825

Williams, Margery. The Velveteen Rabbit: 100th Anniversary Edition. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead. 2022. Doubleday Books for Young Readers. ISBN-10:0593382102, ISBN-13:978-0593382103

Note: This blog was created by Lyn Lacy to share history of children's literature and express personal opinions about innovative picture books. Please respect copyrights of the images which are for educational and entertainment purposes only and are not to be copied for any reason.