Jumanji:

Picture Book Fantasies into the 21st Century

Article 16

by Lyn Lacy

3500 words

Children in mid-19th century America were as delighted as their British counterparts by a fantastic story in which a little girl crawled down a rabbit hole to find herself in an incredible wonderland. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) is regarded as the first English masterpiece written for young people, one that began the “First Golden Age” of children’s literature. Another classic from England at the time was a didactic moral fable, The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby (1862) by Rev. Charles Kingsley, about a chimney sweep named Tom who fell into a river where he met a community of babies who lived underwater and was transformed into one himself.

These novels were the first known stories about children who left their ordinary environments to enter fantasy worlds. The writers also used the literary device of a portal or gateway (the rabbit hole or the river) for the child going in and out of the fantasy. Other fantasies from England followed the same pattern with their own portals: Five Children and It (1902) by E. Nesbit; Peter and Wendy (1911) by J. M. Barrie; The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950) by C. S. Lewis; and James and the Giant Peach (1961) by Roald Dahl. The first American author to write this type of fantasy novel was L. Frank Baum in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), in which the portal was the door to Dorothy’s house opening into Oz. Charlotte’s Web (1952) by E. B. White and illustrated by Garth Williams is also an American classic but about talking animals, a subsection of the fantasy genre that does not rely on portals or even magical worlds.

Over half a century after Oz, Maurice Sendak created another American fantasy—not as a novel but as a picture book that is now also considered a masterpiece in children’s literature, not only because of its art but also because of its ideas that were new to the genre. Previously discussed in Article 4 was Sendak’s honesty in Where the Wild Things Are (1963) about a child’s anger, rebelliousness and disobedience, subjects that were unheard of in picture books at the time,. And noted in Article 14 was the public outrage in the 1960s over his monstrous wild beasts that were going to scare children with their terrible roars, teeth, eyes and claws. Now a third Wild Things controversy from that time was that Max’s bedroom was taken over by a weird, menacing forest that some adults thought might haunt children lying in their own beds.

Sendak’s forest had a twist on the tradition of a portal—Max had already shut the door to his room. The fantasy world simply appeared in his solitary environment:

“That very night in Max’s room a forest grew and grew and grew

until his ceiling hung with vines and the walls became the world

all around and an ocean tumbled by with a private boat for Max…”

Sendak did not employ a passageway in the back of a wardrobe, a rabbit hole to fall into or any other entry into a magical land. The brilliance of Sendak’s transformation was that for Max the ordinary faded away to be replaced by the fantastic and when the transformation was complete, the boy was just there, dancing by the light of the moon before, quite abruptly, he was in the sailboat. The magical forest was created by Max’s own imagination, or as Sendak has said—“Children turn to fantasy: that imagined world where disturbing emotional situations are solved to their satisfaction.”

A clue why Sendak subtly—and successfully beyond his wildest dreams—broke with fantasy’s tradition of portals may come from his own description in later years of how he had gotten his book ideas. As a young man in Brooklyn, he has said, he sat at his apartment window sketching children at play. He could well have noticed children’s playtime fantasies that were often immediate and accomplished with elastic ease. These are the times kids like to “play pretend,” in which they are instantly someone else, living somewhere else, doing something else. “Let’s be cops and robbers” or “Play like we’re on an island” a child might say, and all the friends immediately take on new personas. Or this idea was a perennial favorite: “Let’s play school and I’m the teacher.” Every one of the children simply is there, without preamble, and often with such intensity that everyday life is transformed by their imaginations into another world. No portal for these fantasies.

A “playing pretend” scenario was what happened in Wild Things -- Max’s fantasy forest came to him, complete with an ocean tumbling by, as a creation of his own making. This was yet a third groundbreaker in Where the Wild Things Are. (In Article 17 will be presented page design as the fourth and final Sendak contribution chosen out of all those that have been written about by other students of the book.)

Twenty years later, Chris Van Allsburg (American, 1949-) created yet another kind of fantasy world in the 1982 Caldecott Medalist, Jumanji (1981). This time, the kids Judy and Peter did not get to sail away, but rather the fantasy world invaded their own comfortable home when their parents were away. Their game board might be thought of as a portal of sorts, but it acted more like a trigger that started and stopped the fantastic events. The idea of familiar rooms turning into a nightmare was a turnabout from the usual in a fantasy and was at the heart of why Jumanji was so scary.

The formality of Van Allsburg’s page design, with text blocked on the left page and black-and-white illustrations framed on the right page, belied the frantic adventure the children were having. With each roll of the dice, a snake was camouflaged on the flower pattern of an upholstered chair or a lion roared from the top of the piano or monkeys wreaked havoc in the kitchen cupboards. One and only one illustration broke out of the picture frame, when rhinos invaded the dining room, and that one small detail brought the action right into the audience’s space in an unnerving way.

Van Allsburg said in his 1982 Caldecott Acceptance Speech, “The inspiration was my recollection of vague disappointment playing board games as a child…Another motivating element for Jumanji was a fascination I have with seeing things where they don’t belong.” This element of surprise in a fantasy world is a contribution that Van Allsburg and Sendak have in common. Just as in Where the Wild Things Are, in Jumanji as well as in other early books by Van Allsburg— The Garden of Abdul Gasazi (1979), Ben’s Dream (1982) and The Wreck of the Zephyr (1983)— twists at the end implied that the plots are indeed more than just dream sequences.

Other picture book authors and illustrators like John Burningham (British, 1936-2019) were also students of children, as in Come Away From The Water, Shirley (1977). Gail E. Haley (American, 1939-) created magical fantasy worlds in Birdsong (1984) and Sea Tale (1990). Matt Faulkner (American, 1961-) imagined The Amazing Voyage of Jackie Grace (1987) that began in Jackie’s own bathtub. After The Loathsome Dragon (1987), the extraordinary fantasy career of David Wiesner (American, 1956-) got its start with the 1989 Caldecott Honor Book, Free Fall (see Article 7).

Eric Rohmann (American, 1957-), author and Illustrator of The Cinder-Eyed Cats (1997) pictured a lush, multi-dimensional fantasy world into which, like Max, a young boy sailed his boat. However, here magical ocean creatures rose from the sea to dance with cinder-eyed cats on moonlit nights. Rohmann has written, “As a teenager I discovered Robert McCloskey, Wanda Gag, Virginia Lee Burton, and Maurice Sendak. I was certainly influenced by Sendak, and after I finished the book I realized it had a boy in a boat going to an island. The fish scenes, however, came from watching TV nature shows.”

In the 21st century, authors and illustrators below continued to create works of fantasy in picture books that were exquisitely beautiful or crazily suspenseful, with or without portals.

2002 Chris Van Allsburg (American, 1949- ), Author and Illustrator. Zathura, Houghton Mifflin, 32 pp, 9” x 11.9”

Twenty years after Jumanji , Van Allsburg’s sequel revealed what happened to the two Budwing boys after they ran away with Judy and Peter’s board game. This time the challenges were intergalactic, involving gravity, time travel and a black hole. The illustrator’s masterful black and white imagery told a surreal story about outer space coming up close and personal in a homey room with old-fashioned patterned wallpaper. Van Allsburg also released Probuditi! (2006), done in sepia and a biography in black and white, Queen of the Falls (2011). See Articles 7 and 16.

2003 John Burningham (British, 1936-2019), Author and Illustrator. The Magic Bed, New York: Knopf, 48pp, 11.6” x 9.4”

When Georgie said a secret word every night, his bed carried him high over the city to a meadow, a jungle, an island, the sea or right up into the sky. Burningham has said, “Drawing is like playing the piano; it’s not a mechanical skill like bricklaying, and you have to practice constantly to keep it fluent. Even after 40 years it doesn’t get any easier.” Burningham followed up with It’s A Secret! in 2009.

2003 David Shannon (American, 1960-), Illustrator. How I Became A Pirate by Melinda Long, New York: Harcourt, 44pp, 8.5” x 11”

Pirates asked Jeremy Jacob to come with them to bury a treasure chest because he was such a good digger for his sand castle. He got homesick after awhile (like Max), and they ended up burying the treasure in Jeremy Jacob’s own back yard. Shannon says he likes stories with bad guys in them because "you need both sides for a good story….I always thought the villains in Disney Movies were really cool", just like Shannon’s cartoon-like Captain Braid Beard and his bug-eyed, snaggle-toothed crew shown every which way, including upside down. He illustrated a sequel, Pirates Don’t Change Diapers (2007) by Melinda Long. See also Article 4 for Shannon’s David books.

2004 Barbara Lehman (American, 1963-), Author and Illustrator. The Red Book, Houghton Mifflin, 32pp, 8.2” x 8”

In this wordless 2005 Caldecott Honor Book, a girl in the city found a red book with a picture of a boy on an island holding a red book with a picture of her in the city. She caught a bunch of balloons that lifted her high above her city and straight to his island. Lehman followed up with fantasy trips in The Museum Trip (2006), The Rainstorm (2007) and Trainstop (2008).

2005 Eric Rohmann (American, 1957- ), Author and Illustrator. Clara and Asha, Roaring Brook Press, 40 pp, 9.7” x 10.3”

Clara had an imaginary friend, an enormous fish called Asha, who smiled, introduced herself and glided in through a window at bedtime. The two played games, had a bath, a tea party and a Halloween dress-up before sailing out the window for a glorious romp in the night sky. Asha was reminiscent of the larger-than-life fish friend in the illustrator’s Cinder-Eyed Cats and the soaring escapade of a bird in his 1995 Honor Book, Time Flies. See also Article 7 for 2003 Caldecott Medalist My Friend Rabbit.

2006 Peter McCarty (American, 1966-), Author and Illustrator. Moon Plane, Henry Holt, 40 pp, 9.4” x10.4”

A boy saw an airplane flying overhead and imagined it flying to the moon and even learning to fly it himself. When his adventure was over, he landed at home, where his mother was waiting for him, like Max’s mother. The atmosphere of a silent movie fit the nostalgic mood of a time when prop planes ruled the sky. The soft black and white illustrations are reminiscent of McCarty’s Night Driving (2001) by John Coy. See also Jeremy Draws A Monster (2009) in Article 14.

2006 David Wiesner (American, 1956-), Illustrator. Flotsam, Clarion, 40 pp, 11.2” x 9”

The intriguing 2007 Honor Book showed a boy’s exploration of fantastic underwater scenes and portraits of 19th century children, all captured on film in an old camera. The boy took his own picture and hurled the camera back into the sea for another child to find. To cover all the details in this twisted tale, no less than 86 illustrations occupied various sizes of vertical, horizontal or square panels and single or double page spreads. See also Article 7 for his Caldecott winners, Tuesday (1991) and The Three Pigs (2001).

2006 Uri Shulevitz (American, 1935-), Author and Illustrator. So Sleepy Story, Farrar, 32pp, 10.4” x 9.2”

In a sleepy sleepy house all bathed in blue and gray, music drifted in a window to wake up a sleepy sleepy boy and all his sleepy sleepy things. In a delightful series of wordless illustrations, the house lightened up with yellow and orange as the music got louder (some notes on the staff were blowing their horns) and the table and chairs, pictures on the wall, dishes and teapot, all began to shake, rock and then dance. The mustachioed chair and his coquettish upholstered partner, along with high-stepping plates on the shelves, were as charming as Randolph Caldecott’s frolicking dishes and cutlery in “Hey-Diddle-Diddle.” Shulevitz also created another picture book about a little boy and his room full of things, The Moon in My Room (2003). See also Article 8.

2009 Doug Keith (American, 1952-), Illustrator. The Bored Book by David Michael Slater, Simply Read Books, 32pp, 10.3” x 10.1”

Two bored children annoyed Grandpa with their squabbling until he showed them a hidden stairway that led to a discovery of a mysterious book. The children unfolded its accordion-like pages and fell into a series of hair-raising adventures before returning safely to the library, where they found all the fierce characters had come from Grandpa’s books.

2013 Zuzanna Celei (Spanish, n.d.), Illustrator. Inside My Imagination by Marta Arteaga with Jon Brokenbrow, Translator, Madrid: Cuento De Luz, 24pp, 8.2” x 10.2”

Enter through the door and find words in a girl’s story that became her thoughts, magically freeing her to journey into her own world of elves, fairies, unicorns and clouds forming shapes, from which new stories came forth from more jumbled words and thoughts.

2013 Aaron Becker (American, n.d.), Author and Illustrator. Journey, Candlewick, 40 pp, 9.8” x 10.9”

Becker’s wordless trilogy began in Becker’s 2014 Caldecott Honor Book, Journey, in which the family had been so busy that the bored little girl drew the door with her red sidewalk chalk and slipped through into a Max-like forest. She drew herself a small boat to meander downstream to a magical walled city, where the twisted Escher-type canal emptied her out right into the sky. She drew herself a hot air balloon to go flying through an armada of steampunk airships. She released an exotic bird held captive on one of the ships, and together they flew back home. In the next book, Quest (2014), the girl, a friend and the beautiful bird returned to the walled city to rescue a king, and in book 3 Return (2016) the father followed his daughter through the portal to share in her magical adventures. See Article 7.

2016 Carson Ellis (American, 1975-), Author and Illustrator. Du Iz Tak? Candlewick, 48pp, 10.1” x 12.1”

Ellis created in her 2017 Honor Book a turnabout scenario in which a real little plant in springtime sprouted in a fantasy world of some bespectacled, well-dressed insects speaking their own language. In this ingenious multi-faceted tour de force, the entire plot unfolded on a firm horizontal baseline for the gentle figures of the insects and pill bug “Icky.” As the plant grew taller, the group banded together to build a fort in its leaves, only to have it destroyed first by a spider’s web, then by a bird. As winter came, the scene reverted to emptiness on its horizontal base but with springtime, new plants sprouted and a new bug arrived, hinting at a new story. All figures were backlit on a white background except for two nighttime scenes; the illustrator explained, “I don’t like making cluttered compositions. I want things to feel airy and spacious, not busy. I don’t want elements of the composition to compete.” See also Article 7.

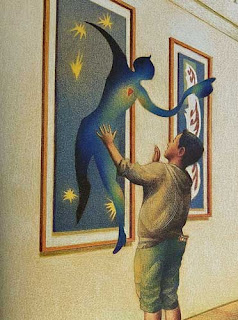

2018 Raúl Colón (Puerto Rican American, 1952-), Author/ Illustrator. Imagine! Simon & Schuster, 48 pp, 9”x11”

Welcoming fantasy characters into the real world did not come any better than in this wordless book. Seven iconic figures from famous paintings on MOMA’s walls jumped down to join a boy on a tour of New York City. Dancing all the way were characters from Rousseau’s The Sleeping Gypsy, Picasso’s Three Musicians, and Matisse’s Icarus. On the way home from his adventures, the boy created his own art on a wall. Colón worked in watercolors and lithographic pencils, creating texture with stippling and cross hatching, with muted colors and striking patterns. By superimposing small illustrations on top of his spreads, the artist fleshed out the sequence of events in the filmic style of graphic novels.

2018 Jihyeon Lee (South Korean American, n.d.), Author and Illustrator. Door, Chronicle Books, 56 pp, 9.4” x 12.4”

In this wordless book, a boy found a key to a portal that opened into a magical world of intriguing, playful creatures. Lee's first wordless book, Pool (2015) was about a shy boy's jump into a crowded public pool, where he dove deep to a forest of fantastic aquatic creatures and plants. In both books, the real, ordinary world was rendered in delicate black, white, and gray line drawings that contrasted with the joyful fantasy worlds, drawn with vivid colored pencils and pastels.

2019 Erin E. Stead (American, 1982-), Illustrator. Music for Mister Moon by Philip C. Stead, Neal Porter Books, 40 pp, 7.7” x 11.2”

Harriet Henry (called “Hank”) was too shy to play her cello for “crowds of people all dressed up like penguins” until she made friends with the moon, whose kind demeanor and need for adventure imbued her with self-confidence. How she managed to get to that point was all her own doing, a proactive and determined little gal with an enormous imagination that fueled every step of the fantasy. In their signature style, the Steads offered another gentle, heartwarming story in the 2011 Caldecott Medalist, A Sick Day for Amos McGee (2010), in which fantasy walked right in the front door when Amos missed work at the Zoo, so an elephant, a rhino, a tortoise, a penguin, an owl and the tiniest of birds came to find out what had happened to their friend. See Articles 7 and 15 for more about the Steads.

2019 Christian Robinson (American, n.d.), Author and Illustrator. Another, Atheneum, 56 pp, 9” x 11”

As a little girl and her cat curl up in bed, a portal opened up in the room and another cat appeared to lead them on a delightful journey into another world. They not only met other children but their own alternate selves. Was it all a dream or perhaps a parallel universe? In this wordless book, vibrant shapes danced and figures played upside down, inviting the reader to turn the page around.

2019 Barbara McClintock (American, ), Author and Illustrator. Vroom!, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 32pp. 10.4” x8.1”

Sendak’s Max might well have met his match in little red-headed Annie, who got out her helmet, gloves and spiffy race car to go vrooming! out the second-floor window of her room. This girl loved to drive fast—and McClintock means fast—as she ate up the miles in her extraordinary adventure across farmland, up a mountain, over a river, and through a city before gliding back into her room just in time for Dad to read a story about cars for bedtime.

Ordering Bibliography

Arteaga, Marta. Inside My Imagination. Translator Jon Brokenbrow,

illustrated by Zuzanna Celei, 2013, Madrid: Cuento De Luz

Becker, Aaron. Return. 2016, Candlewick

Burningham, John. The Magic Bed. 2003, Knopf

Colón, Raúl. Imagine! 2018, Simon & Schuster

Ellis, Carson. Du Iz Tak? 2016, Candlewick

Lee, Jihyeon. Door. 2018, Chronicle Books

Lehman, Barbara. The Red Book. 2004, Houghton Mifflin

McCarty, Peter. Moon Plane. 2006, Henry Holt

McClintock, Barbara. Vroom! 2019, Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Robinson, Christian. Another. 2019, Atheneum

Rohmann, Eric. Clara and Asha. 2005, Roaring Brook Press

Shulevitz, Uri. So Sleepy Story. 2006, Farrar

Slater, David Michael. The Bored Book. illustrated by Doug Keith.

2009, Simply Read Books

Stead, Philip C. Music for Mister Moon. Illustrated by Erin E. Stead.

2019, Neal Porter Books

Van Allsburg, Chris. Zathura. 2002, Houghton Mifflin

Wiesner, David. Flotsam. 2006, Clarion

Note: This blog was created by Lyn Lacy to share history and express personal opinions about innovative picture books. Please respect copyrights of the images which are for educational purposes only and are not to be copied for any reason.

No comments:

Post a Comment